Duck Threading: Coda

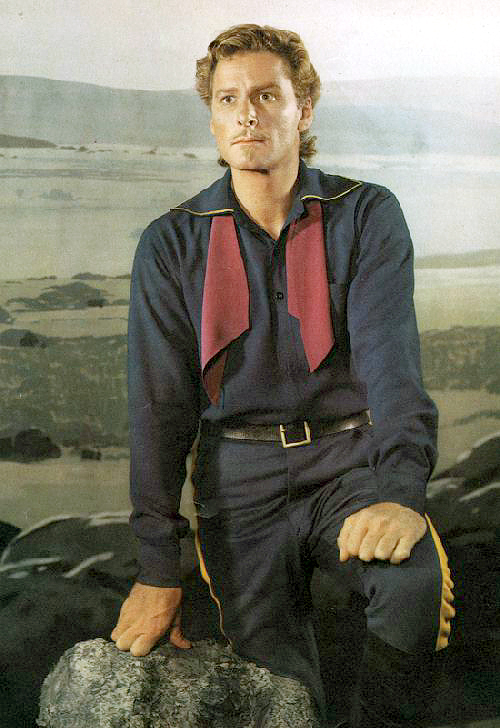

So apparently, Errol Flynn, living in magnificent, coddled stardom in the Hollywood hills, developed some bizarre ways of passing the time in those long, perfumed, barbiturate-hazed afternoons in between movies.

Ducks can't resist a bit of fat. It's well known. Put some lard in front of them, a piece of dripping, bacon rind, even a manky old knuckle of gristle, and they'll waddle over; quick as a flash, they wolf it down. The kicker is that the waterfowl digestive system is ill equipped to cope with the richness of an animal lipid diet. The fatty matter passes right through, and quickly.

Flynn, in his state of filmstar ennui, was quick to exploit this deficiency of barbary gut function. Gathering a pen of pretty mallard, he would throw in a lump of fat on a string. In a blink, duck one gobbles it up. Here's the science part. Nature soon takes its course and the deposit in question is hanging, on its string, out of the unfortunate bird's puckered anus. Can it be long before another victim takes the bait? No sir.

Well, before you know it, you have a trainable string of ducks. A duck thread. An aquatic avian daisy chain. Why Flynn, star of such Golden Era classics as The Adventures of Robin Hood and They Died with Their Boots On, would routinely perform these, let's face it, cruel acts, is a matter of some conjecture among film historians and animal husbandrists.

Of course, a well-trained string of ducks might be immensely useful. They could be used to fly up in unison and retrieve a cricket ball from your roof, passing it beak to beak down the chain into your butler's waiting hands. Perhaps later, in a fit of pique, you might hit the ball down one of Los Angeles' many storm drains. No problem. Ducks on a string? Retrieving's their thing! My favourite theory is that Flynn used to like to go up to a high point, say, the Hollywood sign, and fly the ducks like a huge, articulated living kite. Imagine the fun.

However, the training aspect raises a somewhat sombre and distressing question. If a duck in the middle of the thread, say duck 6, were to die (through scurvy, or duck gout, or though having his neck wrung for being less obedient and trainable than its fellows), how was it disposed of? Was it left to rot and fall off naturally? I don't like this hypothesis because it's gross. Some have suggested that Flynn would simply snip out that section of line and tie it back together. This solution seems inelegant and not in keeping with the otherwise simple and beautiful nature of the endeavour. My (unproven) hypothesis is that Flynn, not content with being a pioneer in the art of duck threading, was also an early exponent of the science of Cybernetics. Should one of the ducks die, or show signs of illness, he would gradually replace its sick and morbid components with plastic and metal articulations, ball bearing gimbals, miniature servo motors, and small valve-based force feedback governors.

It's not inconceivable then to imagine Flynn's waterborne deathbed: The sound of waves outside, the bobbing of a gentle swell, the cool hand of his underage partner, Beverly, on his brow, and the grinding and clicking of seventeen mechanised ducks on a string, jostling irritatingly in the master cabin of a fading matinée idol's 70 foot yacht, berthed in sunny Vancouver Sound.

Notes:

Based on a post gig hotel bar conversation in Berlin with my ex Electric Shocks bandmate, Dan.

Originally published on draGnet 4.0, 14 February 2005.

comments powered by Disqus